The Significance of Personalized Nutrition in Modern Science

Introduction

The idea that one diet does not fit all has become central to contemporary nutritional science. Researchers now recognize that the same meal can produce widely different effects depending on a person’s genes, daily habits, and surroundings. This article explores why individualized dietary guidance matters, how it is developed, and what it could mean for everyday health.

The Concept of Personalized Nutrition

Defining Personalized Nutrition

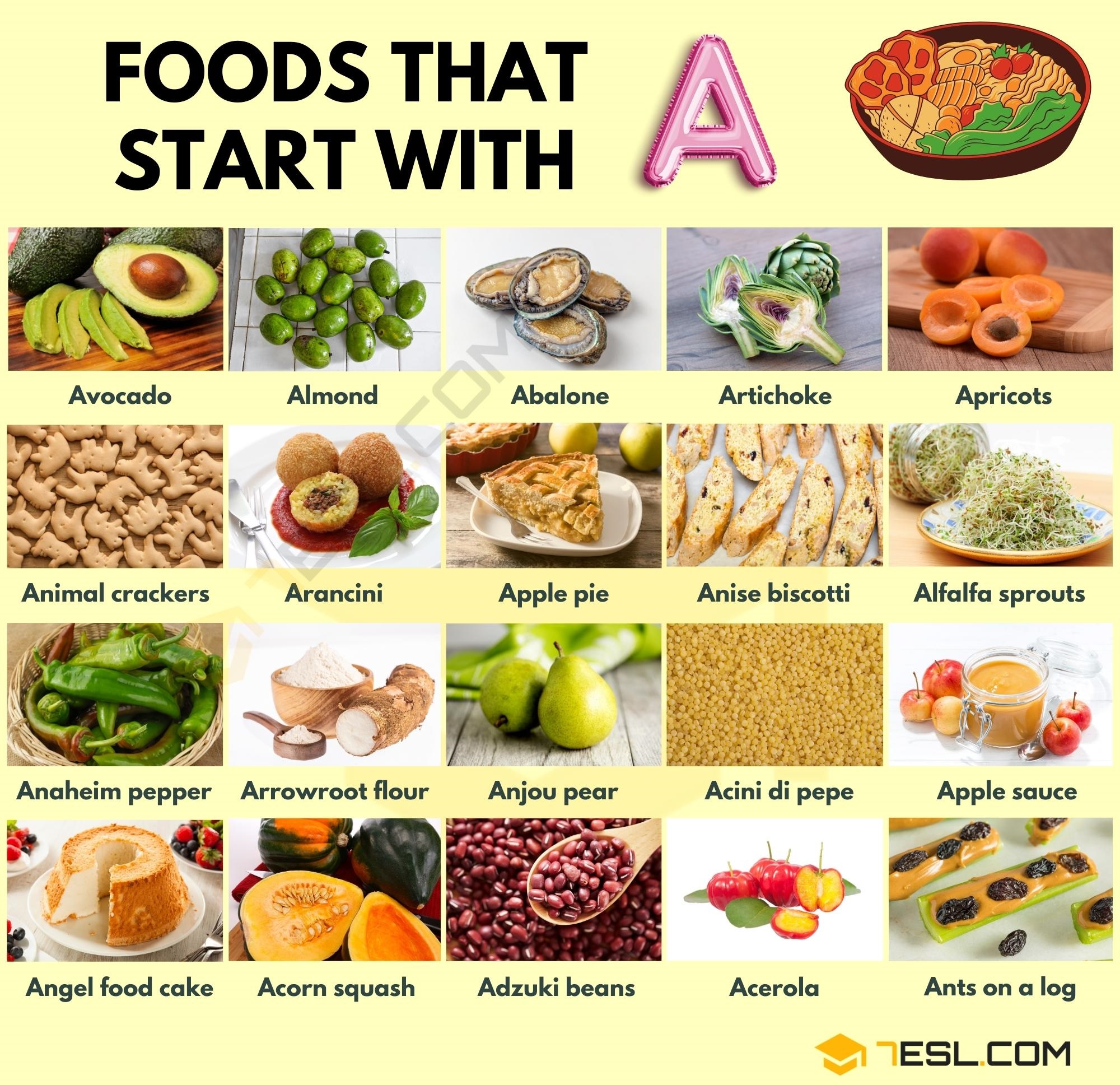

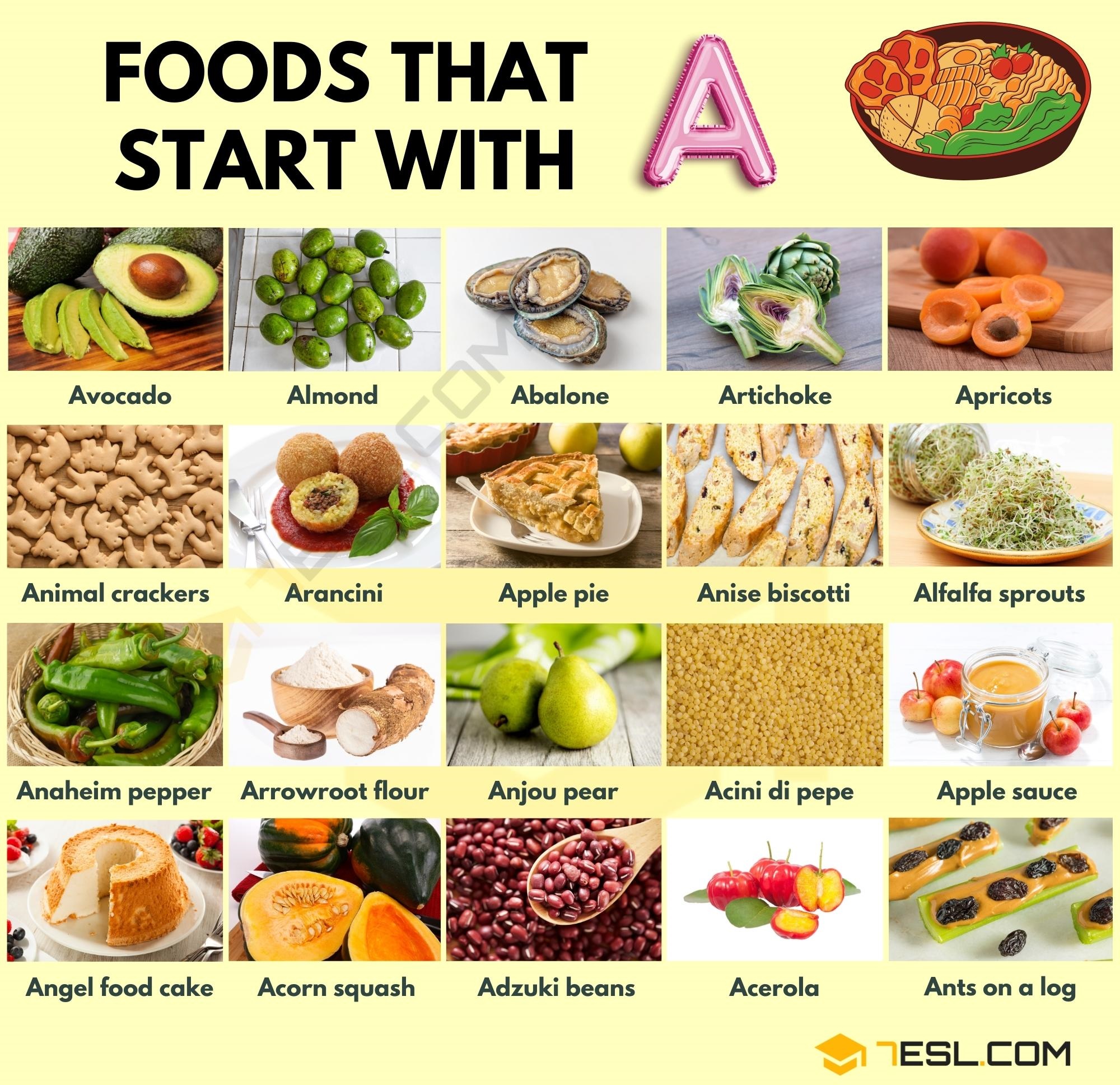

Personalized nutrition rests on the simple premise that each body interacts with food in its own way. Variations in digestion, metabolism, and lifestyle mean that identical plates can yield distinct outcomes for different people, underscoring the need for customized eating plans rather than universal rules.

Genetic Factors

Inherited traits influence how vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients are absorbed and processed. Small differences in DNA can alter everything from lactose tolerance to the speed at which caffeine is cleared, shaping both requirements and responses to everyday foods.

Lifestyle and Environmental Influences

Activity level, sleep quality, stress, and even local air quality can modify nutrient needs. Someone who cycles to work may oxidize fats differently from a person with a desk job, while produce grown in mineral-rich soil can offer a denser micronutrient profile than the same crop grown elsewhere.

Implications for Tailored Guidance

Customized Eating Plans

When practitioners weigh genetic data alongside lifestyle records, they can design menus that match personal demands. Such targeted advice often improves energy, supports healthy aging, and lowers risk factors for common chronic conditions.

Nutritional Genomics

This discipline examines how specific gene variants interact with dietary components. Identifying these links allows clinicians to flag individuals who might benefit from extra folate, limited sodium, or higher omega-3 intake, turning genetic insight into practical meals.

Nutritional Epigenetics

Daily choices can leave reversible marks on DNA that dial gene activity up or down. Diets rich in colorful plants, for instance, supply compounds that may encourage protective gene expression, offering a long-term shield against certain disorders without changing the genetic code itself.

Challenges and Limitations

Data Complexity

Translating genetic reports and lifestyle logs into clear, safe advice demands expertise. Variants often interact in unexpected ways, and science is still mapping the full landscape of gene–diet relationships.

Cost and Reach

Advanced testing and one-to-one counseling remain pricey, limiting access for many households. Streamlining technology and expanding insurance coverage will be key to broader adoption.

Privacy Concerns

Storing and sharing biological data raise questions about consent and security. Robust safeguards and transparent policies are essential to maintain trust as the field grows.

Future Directions

Tech-Enabled Monitoring

Smartphone apps and wearable sensors already track meals, heart rate, and sleep. Merging these streams with genetic profiles can deliver real-time feedback, nudging users toward healthier choices in the moment.

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

Dietitians, data scientists, and clinicians are joining forces to build evidence libraries and open-access tools. Shared platforms accelerate research and shorten the path from discovery to dinner plate.

Public Education

Clear, engaging messages about individualized eating empower people to ask informed questions and adopt gradual, sustainable changes without feeling overwhelmed by science.

Conclusion

Personalized nutrition shifts the focus from broad prescriptions to the unique dialogue between each body and its food. While hurdles remain, ongoing advances in technology, research, and education promise a future where dietary guidance is as distinct as the individuals it serves, ushering in a new era of preventive health.